Why this book: As a boy and a young man, and like many young men and women then and since, I loved reading Laura Ingalls Wilder’s books about her life growing up on the frontier. I had read another biography of her (by Pamela Smith Hill) which provided some interesting background, but didn’t particularly grab me. This one kept popping up on various lists of great books, and as I was looking for a book to listen to on a long road trip, I thought I’d enjoy revisiting LIW again, so I bought it on Audible.

Summary in 3 sentences: This is part biography of LIW, part a Life-and-Times description of America and the American West from the 1870s into the 1940s, and part a parallel biography of her daughter Rose Wilder Lane who played such an important role in LIW’s life and writing. Because LIW’s parents play such important roles in her books, Prairie Fires begins with the lives of LIW’s parents, and their early lives in Minnesota and Wisconsin, and then moves on to the stories behind the autobiographical novels LIW wrote as the Little House series. The final part of Prairie Fires describes the last 25 or so years of LIW’s life, when she turned to writing her books, how the depression and Roosevelt’s New Deal impacted her and her daughter, their tempestuous but co-dependent relationship, and how it all fits into a fascinating period of American history.

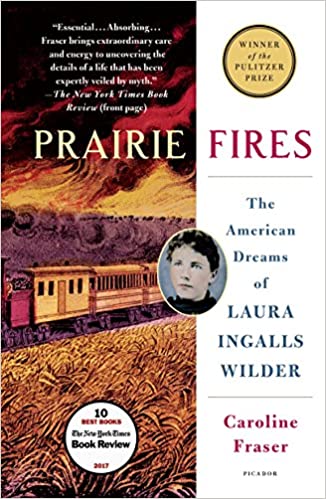

My impressions. Superb! Fraser’s biography of LIW and exploration of her roots, her family and the challenges they had to overcome is a lens through which we look at the maturing of the American West from the 1870s into the first 5 decades of the 20th century. Prairie Fires is the best biography I’ve ever read – right up there with David McCullough’s John Adams for thorough research, a life-and-times story told with sensitively, insight, empathy, and humanity. This is a book about the life of a woman and her daughter – written by a woman – but I didn’t feel like I was reading a book written “for” women. As I got into it, I looked it up, and was not surprised to learn that it received the Pulitzer Prize for biography, and many other awards. Well deserved.

In addition to the “facts” about LIW’s life as she thoroughly researched them, Fraser is not afraid to share her own personal views and perspectives regarding LIW’s life and decisions, decisions and actions of others in her life, and the politics of her times, for which a number of reviewers on Amazon castigate her. Her “warts and all” look at the life of an American Icon did not please some readers. I found her editorializing fair and discerning, evident enough for the reader to sense her judgment, but not at all sanctimonious, and her perspectives are rendered with empathy and understanding. Caroline Fraser is an amazing writer, and in addition to the fascinating story she tells, I loved listening to a master craftsman of English Language.

Audible. I listened to the audible which was excellently rendered, but wish I’d read the book – I can savor a great book better in print; I can mark passages which I find particularly good, which I can’t do on an audible. Fraser refers to a lot of pictures of Wilder and her family in her Prairie Fires, and of course, one doesn’t see those in the audible. I was hoping they’d be in the paperback, but no pics in the paper back – I am not sure about the hardback, but it doesn’t appear so. That is a disappointment.

Fact or Fiction. One of the constant issues in the Prairie Fires story of LIW’s rendering of the Little House book series, was how much truth she should tell in her stories. The Little House series is listed as novels. LIW always insisted that the stories within the books were all true, but not the whole truth. Since she was writing for young audiences, she studiously avoided much of the suffering and hardship she experienced and she didn’t include episodes or experiences which she thought might overly trouble or shock young audiences. Her daughter actively encouraged her to shade the truth to help the books sell better, and Fraser actually found several fabricated incidents in the books, undermining LIW’s claim that it was all “true,” just not the whole truth. It’s evident while the Little House books did include some of the hardship the Wilder family experienced, the true suffering and hardship she and her family experienced were significantly diluted in order to tell an uplifting, happy, and inspiring story.

Suffering. In fact LIW herself and her whole family struggled and suffered a lot – much more than one would think reading the Little House books. That was one of the key messages of Prairie Fires – how indeed hard life was back then, living constantly on the edge, with little or no money in the bank, very little social safety net, vulnerable to the vagaries of weather, nefarious manipulators, the banks, the commodity markets, locust plagues as well as disease and hunger. The Wilder family was often barely one step ahead of destitution. Fraser makes clear that this was sometimes a result of poor decisions on the part of LIWs father – Pa in the books – an otherwise model father and all-round good guy. LIW herself had to work for pittance pay in often unpleasant settings from the time she was about 10 until she married in order to supplement the family’s meager income, to help the whole family survive.

Wilder’s daughter, Rose Wilder Lane. The last half of the book is almost a dual biography of LIW and her daughter Rose Wilder Lane (RWL) This in part because their correspondence is the source of much of Fraser’s content for the biography, but more importantly, RWL was a key collaborator and resource for LIW in editing, shaping and getting the Little House books off the ground and published. It was RWL who inspired and encouraged her mother to write the books; she edited them for her, often improving the quality, and provided valuable suggestions. She was also extremely mercantile and was less interested than her mother in a faithful rendering of what actually happened in her mother’s pioneering experience, ever ready to romanticize and even alter the stories to fit what she believed would best sell. In fact LIW supported much of this “white-washing” of her difficult youthful journey.

One cannot fully appreciate LIW or her work without getting into this very complicated mother-daughter partnership. In fact, it was often difficult for me to read about RWL and her capricious and self-serving decisions, her callously manipulation of her mother, and her calculated use of her mother’s success as springboard for her own career ends. Fraser argued that without RWL, LIW would not have written the books she did, and they probably would not have been as successful nor as widely read as they were. So credit given, where credit is due.

That said, RWL’s bipolar and manic-depressive episodes caused real issues in her relationship not only with her mother, but with others in her life, and her impulsive manic energy routinely seemed to sabotage her relationships. In her manic moments, she charged after new opportunities and new adventures, with apparently little regard for practical matters, and aggressively attacked those who disagreed with her or stood in the way of her projects. In doing so, she spent money she didn’t have, was always in debt, and when the mania subsided, would retreat into suicidal depression. When not depressed and blaming or feeling sorry for herself, she viciously blamed other people and institutions, and circumstances for her problems. She also became a well known political figure in libertarian circles and a great proponent of individual freedom and independence, an opponent of government regulation and intrusion into people lives.

Rose Ingalls Wilder was indeed an intelligent and talented but troubled and unstable woman. As a daughter, as well as an agent and collaborator, she was both a great resource and significant challenge for Laura ingalls Wilder. The tension between mother and daughter in the nurturing along, editing and publishing of the Little House books is an ever-present theme in Prairie Fires. There was mutual love and respect, and at times a co-dependency between the two, but it was very often difficult for both of them.

Politics, then and now. As Fraser describes RWL’s libertarian crusades and LIWs general agreement with her philosophy, I was struck by similarities with today’s philosophical tensions between the left and the right. Though LIW was not as strident nor proselytizing about her political beliefs as RWL, both were strong opponents of Roosevelt’s New Deal. Fraser describes how their anti-New Deal politics were part of a strong midwestern sentiment that hated Roosevelt and his relentless expansion of his and the US Government’s authority and reach.

LIW grew up in a world of small and limited government, few government programs for the poor and working people, and therefore, people made their own decisions, and were expected to live and deal with the consequences – relying on family, friends, and neighbors for assistance if needed. Fraser offers many examples of “government men” intruding into the lives of farmers and working people, telling them what they had to do, how they had to live, because the the bureaucrats in government said so. LIW stoically believed in the basic independence and responsibility of individuals and resisted and resented governmental intrusion into their lives except to provide basic services for the common good, and to level the playing field. RWL took that sentiment to the next level, writing editorials and books extolling the free American spirit and eviscerating New Deal and government over-reach. The mistrust and antipathy between both sides in this debate was extreme. Sound familiar?

Mansfield Missouri. In Prairie Fires we learn of how the Ingalls family of Laura’s youth and later the Wilder family of her, Almonzo (her husband,) and Rose, dealt with setback after setback, relying on friends and family to get by day-to-day, frequently having to pack up and move to start all over again. During the depression of 1894, when much of the country was barely surviving, LIW and her husband and daughter finally gave up trying to make a living farming in South Dakota, and left De Smet, South Dakota with little more than a horse and covered wagon to their name, and headed for Mansfield, Missouri where they settled down and lived for the next 60+ years. In Prairie Fires we learn of life on a farm outside of a small Missouri town and how the Wilders barely scraped by for decades, until finally in the last couple of decades of their lives, they achieving some financial security, after LIW in her 60s, published The Little House in the Big Woods, the success of which spawned eight follow-on novels.

End of Life and Legacy. The final part of the book tells the story of LIW in her 70s, and Almonzo in his 80s finally having the freedom to live without great concern for money to pay the bills. LIW gets recognition and accolades from all over the world, and she and Almonzo are able to travel a bit by car to visit friends and family in South Dakota and even to go out to California. As they both got older and energy waned, these activities subsided. Almonzo’s health begins to fail and he dies at age 92, and LIW spends her last 10 years comfortable but in poor health, with little energy to take advantage of many offers she receives to bask in her success and public acclaim. Living alone but with support from friends, she spent her last years enjoying her farm, answering fan male and reflecting on her life. She died in 1957, a few days after her 90th birthday.

The last chapters of the book are about her legacy and the how her estate, inherited by RWL ended up after RIW’s death in the hands of one of RWL’s protégés, who was a lot like RWL – ambitious without conscience. He personally profited from the Little House books for which he had done nothing, and ignored the desires LIW stated in her will for how the long term proceeds and royalties from her work were meant to support the library named for her in Mansfield. Mo. All of this eventually led to the Little House on the Prairie television series in the 1970s, which, though it distorted much of LIW’s work and message, it significantly increased her popularity and readership. The stories Fraser tells of the television series are amusing and don’t reflect well on Michael Landon.

In conclusion, I was really impressed with this book, and in addition to learning a lot about the life of a girl I had a school-boy crush on from reading her books, I also learned a lot about America – some of the ugly truth about our frontier heritage, and life in midwest America in the later 19th and first half of the 20th century.

Pingback: The Wyoming Lynching of Cattle Kate 1889, by George Hufsmith | Bob's Books