Why this book; I had read this book over 30 years ago and recall being moved and finding the story fascinating. On my recent trip to the Inner Hebrides with my son, my interest in this remote island, nearly 100 miles west of the outer Hebrides, was renewed. So I purchased it and read it again.

Summary in 3 Sentences; This remote small Island has had isolated people living on it for thousands of years, barely surviving in an extremely austere environment. Recorded history of the Gaelic speaking inhabitants and how they lived only goes back about 300 years and this book is the recognized best source on how those people lived, what led to the decision in 1930 of the 30 or so remaining inhabitants to leave. And the book concludes with what happened to those who left, how they sought to integrate with a very different world, and how the British and Scottish governments and Trusts have sought to preserve the heritage of this unique island.

My Impressions: As noted, my second time reading this book – the first time over 3 decades ago and I only remember a few things. – but I do remember how fascinated I was with the descriptions of this ancient Gaelic crofter culture isolated for centuries from the mainstream culture of Britain and Europe. It was the last remaining hunter-gatherer society in Europe and there are scant records of how these people lived prior to the 17th century when the earliest chroniclers visited.

St Kilda is the main small island in a grouping of rock outcroppings out int the Atlantic Ocean, about 80 miles west of the closest land in the Scottish Outer Hebrides, and it’s population varied from at a high point about 140 to less than half that before the final decline and decision to evacuate the island in 1930. This book describes the culture of St Kilda from the 19th century when mainstream Scotland became aware of St Kilda and Clan MacLeod of Skye assumed proprietorship over the island, which included Clan leader-like responsibilities for its inhabitants. Archeologists are still finding evidence of human habitation on St Kilda going back a millennia before the first appearance of St Kilda in Norse records a millennium ago

The LIfe and Death of St Kilda begins by describing the sad and final exodus of the inhabitants in 1930. Following chapters explore and describe the culture – how the people lived, how they lived mostly on the birds they killed in their nesting grounds on the cliffs and rocks on the group of islands. The author describes their social mores, how it was a very communal society, all sharing in the bounty and the sufferings that came with living on the island. There are chapters on how the Church of Scotland sent severe ministers to live on the island to ensure that the inhabitants paid humble obeisance to an angry God, and forbade all forms of fun and joy – no dancing, singing, music, etc in the same way our Puritan forefathers forbade any activity that wasn’t working to survive or worshipping the Lord. Life was hard enough – these ministers ensured that it stayed hard

The author describes the slow influence that increased contact with mainland society during the 19th century, had on the islanders. St Kilda eventually was provided a teacher to teach reading and English to the children, and this basic education was augmented by religious education (reading the bible) by the resident ministers. Reading gave the islanders increased access to newspapers and other books that increased awareness of life beyond St Kilda, along with increasing visits from fishing trawlers, the factor from Skye and eventually tourists interested in this primitive Gaelic culture. Eventually visitors wanted to buy their goods – knitting and other crafts and items with money, which the islanders had never needed in their barter culture. Money and its value was new and had a subtle but profound influence. And as the islanders learned of opportunities outside St Kilda – from stories that visitors shared and from the occasional emigrant from St Kilda who returned to visit, or shared stories in their letters, young people started to leave.

One chapter that I remember most from when I first read this book was the very high child mortality rate – above 60%. There were women who’d given birth to 10 babies and lose 8 before being a month old. When medical people on the mainland learned of this, they wanted to find out why and prevent these tragedies, but the islanders, led by their very conservative minister wouldn’t cooperate, believing that these deaths were God’s will, His plan to keep the population within what the island could support, and it was not for man to interfere. Eventually it was determined that the deaths were caused by how they stored milk for the children, in containers unknowingly contaminated with the bacteria tetanus infantum, and as they gave babies milk from these containers, the children quickly developed tetanus and died within days. The tragedy of so many babies dying so soon after being born is unimaginable, but it had been going on for centuries and was just assumed by the St Kildans to be simply the way it was supposed to be. Just as tragic to me is the resistance the minister encouraged to finding out why.

The book concludes with what happened to St Kilda after the last inhabitants left – the challenges they had in adapting to life on mainland Scotland. Also, during the 20th century the British Military built a small station on this remote outpost in the Atlantic for monitoring naval and air activity approaching the UK, and for supporting various exercises and equipment testing. St Kilda and the ruins of the small village on Hirta has in the last half century become a tourist destination, and is now largely controlled by the National Trust of Scotland in cooperation with the military which continues to maintain a presence there. The National Trust has refurbished many of the homes that were abandoned, and created a small museum to serve as a monument to the people and culture that once lived there. Additionally, archeologists are exploring, and turning up evidence of people who lived there during the Iron Age and perhaps before.

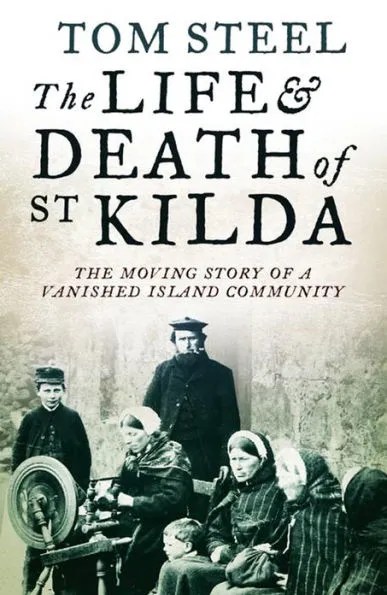

In the various bookstores I visited in Scotland, I found numerous books on St Kilda, but one of the booksellers told me this is the most comprehensive and the best. Tom Steele first published this book in 1975 after doing extensive historical research, and also was able to interview many people who had lived on St Kilda before it was evacuated. He updated the book in 1988 and then, after his death, his relatives gave a final update in 2011. For those interested in knowing more about St Kilda, there are some impressive videos and short pieces on St Kilda on youtube.